A Visual Analysis of Markings found on First World War German and Austro-Hungarian Artillery v.17 – 14/11/2020

![]()

7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A. Nr. 315.* (1897. converted 1907.) Kp. – Seymour, VIC

7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A. Nr. 1559.* (1898. converted 1906.) Kp. – AWM (RELAWM05023), Canberra, ACT

15-cm K. 16 Nr. 103. 1918. Kp. – Scoresby, VIC.

15-cm K. 16 Nr. 135. 1918. Kp. – AWM (RELAWM05044), Canberra, ACT.

7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A. Nr. 1274.* (1897. converted 1906.) Kp. – Coonamble, NSW

10.5-cm l.F.H. 98/09 Nr. 1457. 1915. Rh.M.F. – AWM (RELAWM05063), Canberra, ACT

21-cm lg. Mörser 16 Nr. 960. 1917. Kp. – AWM (RELAWM05037), Canberra, ACT; 21-cm lg. Mörser 16 Nr. 1257. 1918. Kp. – AWM (RELAWM05008), Canberra, ACT.

7.7-cm F.K. 16 Nr. 14137. 1917. F.M A. – AWM (RELAWM05047), Canberra, ACT

15-cm S.K./40 Nr. 505L. 1900. Kp. – Australian Army History Unit, Bandiana, VIC

10.5-cm l.F.H. 16 Nr. 14607. 1918. MAN.N. – Watsonia, VIC.

10-cm K. 14 Nr. 378. 1916. Kp. – AWM (RELAWM05002), Canberra, ACT

7.7-cm F.K. 16 Nr. 121. 1918. GGFJ. – Castlemaine, VIC

7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A. Nr. 4725. 1906. Gg. Sp. – Port Kembla, NSW

Schußstellung – Fahrstellung [Firing position – Driving/transport position])

Purpose of Survey

The purpose of this survey is to record and understand manufacturing and component markings found on First World War German and Austro-Hungarian artillery pieces (Figs. 1–6).

The identification and analysis of components and their markings can facilitate a greater understanding of the artefacts’ cultural biography.[1]Harley (1987); Gosden and Marshall (1999); Kopytoff (2010); Cornish (2004); Stengs (2005). That is, its nature, history and use over time. However, generally, the production, manufacturer and date, component assembly, use and replacement over time, are seldom documented for such objects, as any documentation has become either de-contextualised from the artefact or has not survived. Consequently, the artefact itself has become the primary source of evidence for such activities.[2]Pearson (2000); Connah and Pearson (2002); Pearson and Connah (2009); Pearson and Connah (2013); Pearson and Browning (2015); Pearson and Vanderkelen (2018); Pearson (2019: 462–469). The investigation of artillery: ‘can be understood as the result of many activities including the combination of construction, destruction, repair, alteration and reinstatement, which may occur at specific chronological intervals’.[3]Pearson (2000: 51). An artefact is a document of its own history; therefore, the consideration of the sequential development of an artillery piece can be based on recording and understanding diagnostic elements such as the variability of components as well as markings found on this componentry, with the help of some specialised and generic historical documentation when it is available.[4]Die feldkanone 16. (F. K. 16) (H. Div. 445). 1. Teil. Das feldkanonenrohr 16. 1926 (p.12); Die leichte feldhaubitz 16. (l.F.H. 16.) (H. Div. 446.). 1. Teil Das leichte feldhaubitzrohr 16. 1926 (p.12); Der Artillerist I (Der Kanonier). 1941 … Continue reading Thus the cultural biography of mass-produced artefacts commences with the assembly of numerous interchangeable components, potentially manufactured in different times and places. It continues with its use in an historical context/s, and traces of these activities are ascertainable via physical evidence such: damage and repair; the addition of paint, graffiti and painted markings; and the addition, subtraction, modification and/or replacement of components and their markings. For First World War German and Austro-Hungarian artillery, not only can they gun have been painted in a particular article paint scheme, but many of these components are stamped with distinctive stylistic numbers and symbols applied to components during and after production and these components could be removed and/or conjoined onto to the artefact at any time during its life (at assembly, during field replacement; including component cannibalisation or hybridization during and after the war). This physical evidence provides the mechanism to understand and reconstruct the guns cultural biographies.

The surviving evidence base has been subjected to processes that affect their differential survival over timer since they were created. For example, at the end of the First World War, of those guns that were not destroyed, large numbers of German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish manufacture artillery which were either captured in battle or ceded to the British Commonwealth[5]For example, Great Britain distributed two pools of ceded (surrendered) and unclaimed guns between 1919 and 1920. These were divided up between Great Britain and all the dominions involved in the fighting. Pool 1 consisted of a total of 1036 guns … Continue reading, France, United States and other partners under the treaty of Versailles.[6]For example, Muther (1935a: 201, 210) says at the end of the war in November 1918 there were 2,800 Field Artillery Batteries totalling 11,204 guns and howitzers. A breakdown of the types was as follows: ‘755 Batteries with field gun 16 [7.7-cm … Continue reading Conversely, the Treaty of Versailles set strict limitations of what could be retained by the German army, which included only 288 7.7-cm guns and 10.5-cm howitzers (and no heavy guns), the majority of which would consequently be destroyed during the Second World War.[7]Part V, article 165 of the Treaty of Versailles set strict limitations of 204 7.7-cm guns and 84 10.5-cm Howitzers which could be retained by the German army, many of these guns would consequently be destroyed during the Second World War (Treaty of … Continue reading Guns from the British Commonwealth that were captured in France and Belgium, and sent to Gun Parks before beginning shipped to the Croydon Ordnance Depot (in London). They were then shipped from Croydon to Australian[8]Australian, in spite of the distance and expense of transportation from Britain and Egypt, collected: ‘about 800 guns, 3800 machine guns, 520 trench mortars, 217 motor vehicles, a number of horse vehicles’ [and] tanks’ (CAPD 1917–19: … Continue reading, Canada[9]The Canadian ‘Report of the Award of War Trophies’ dated 18 May 1920 listed: ‘516 captured German guns and howitzers, 304 trench mortars, 2,500 heavy and light machine guns …’ Skaarup (2013: 15). However, a report of December 1942 says … Continue reading, New Zealand[10]Cooke and Maxwell (2013: 48) say that by mid-1919 the NZEF had claimed 165 guns, in addition to guns from Pool 1 and 2. Appendix 2 in Cooke and Maxwell (2013: 424–435) lists entries for 220 guns (from France and Palestine), and 136 Trench Mortars … Continue reading and South Africa (Figs. 7–12). Similarly, America[11]America, for instance, although a latecomer to the conflict, appears to have collected the most, including 3,242 captured pieces of artillery, 4,550 vehicles, 347 aircraft, and other items (Kahn 1921: 5)., France, Belgium and other partners managed their own distributions (Figs. 13–14). A portion of these weapons have survived over the intervening 100 years, the majority albeit in a poorer state than when they were distributed in the 1920s. The others, like many of their European and Britain counterparts were scrapped or destroyed in battle, many during the Second World War. Despite this, the remaining artefacts provide us with an immense body of diagnostic information which can explain the history of the item, the operations of specific units, the use and repair of equipment and the state of manufacturing, as well as the war economy of a particular combatant.

Variability of components as a means for identification

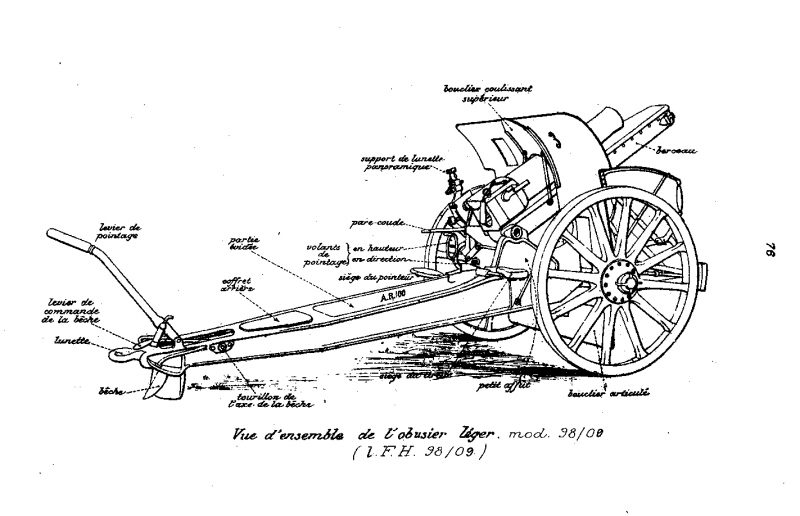

An artillery piece consists of a complex assemblage of thousands of individual components; each is designed to be interchangeable within the designed type/s of weapons. All of these components are included in the broad classification of the weapon, but although guns of the same type look alike, on closer examination numerous variations can be identified. This makes it possible to distinguish between guns of the same type not only by the differences amongst individual replacement parts, but the differences of the various markings, numbers and symbols found on the components.[12]Although beyond the scope of this work, but mentioned above, also includes other evidence available from components such as the application of paint, graffiti, and damage from action, movement and storage as well as changes resulting from later … Continue reading Larger component assemblies, that is groups of many smaller components which when assembled perform a larger function role include: the breech-ring/block; barrel; saddle, sighting equipment; and carriage/trail (Fig. 15). For example, when two identical guns come straight from a factory, they might have identical components and similar markings except for their serial numbers. These same objects in the same operational context might have had different repairs and replacements due to differing use-wear and other damage to components, or to meet the requirements of particular operational context.[13]Pearson and Connah (2009: 236). In addition, following their capture, they might also have received differing treatments including component removal and or replacement. All of these processes give each gun individuality. Thus, the presence of or lack of specific components, and their replacement (as well as their markings) can be a useful diagnostic tool in understanding the cultural biography of an artefact.

Yet, the examination of components to determine what happened to an artefact over time is complex due to factors such as the:

- official upgrade of the gun-type by the introduction or subtraction of designated components (e.g., 7.7-cm C/96 to 7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A.[14]n/A. (New art or new model).). In this instance the guns useful life was extended considerably (Fig. 16);

- introduction or subtraction of components causing the gun to be a variation of type for a specific purpose (e.g. battlefield replacement by detachment where a component is removed (or added) because it may be redundant for a particular operational requirement [such as a field gun being used in an anti-aircraft or anti-tank role] );

- interchange of components due to use-wear and operational requirements before discard or capture (e.g. battlefield replacement) including the cannibalisation of components from a more damaged weapons to keep a less damaged one operational (Figs. 17–19);

- interchange of original components after discard or capture, with the same type of component but with different markings or context (e.g. cannibalisation to replace damaged components to make a more presentable gun);

- introduction of original components which were not present at discard or capture (e.g. cannibalisation in order to make a more complete or perfect gun – the Australian War Museum in the 1920s taking parts of one gun to make a more complete example (Fig. 21–22);

- introduction of components which were never part of the type post-discard or capture (e.g. replacing worn or missing components such as wooden wheels from a wagon or tractor – so the gun is not sitting on the ground) (Figs. 23–24);

Initially, components were replaced by the original users to keep the weapon operational in a battlefield context. However, once removed from this environment, and when the gun is no longer in use as an operational weapon system, components replacement only affects its basic functionality and presentation (e.g. the artefact probable does not now need to operate as per the requirements of a battlefield context).

Variability of markings as a means for identification

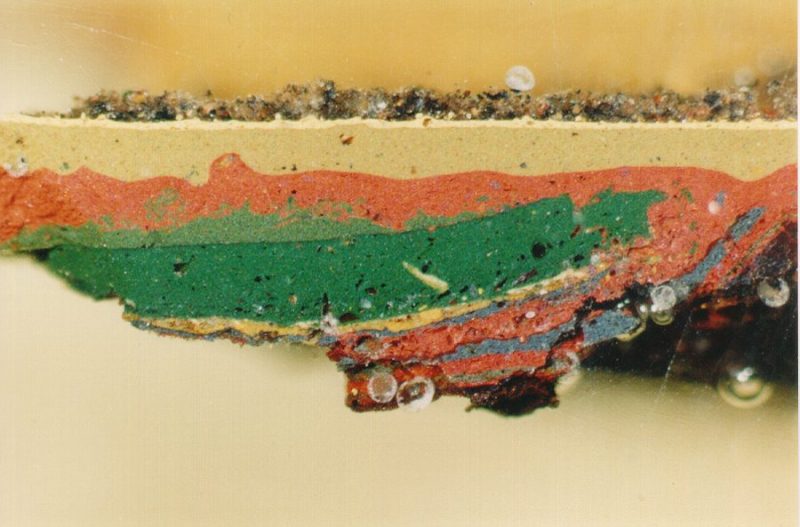

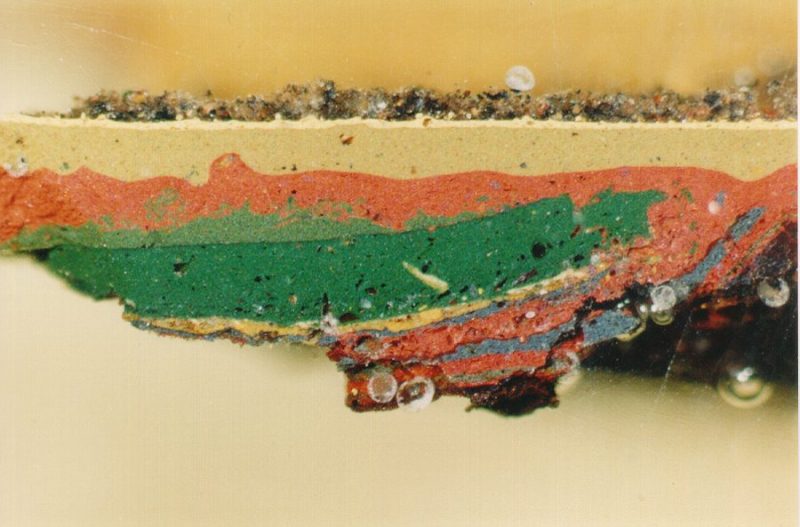

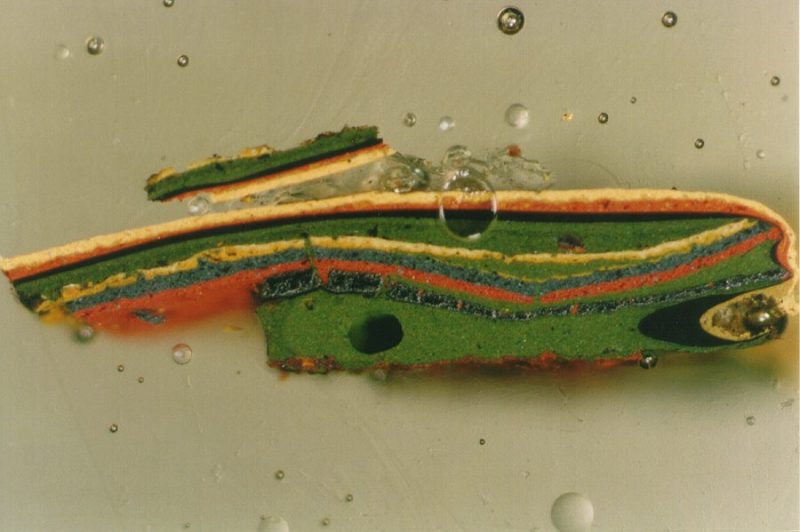

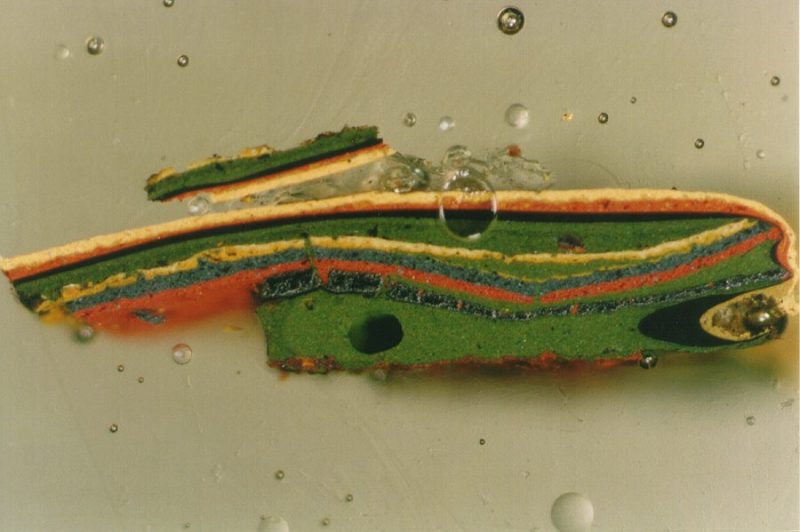

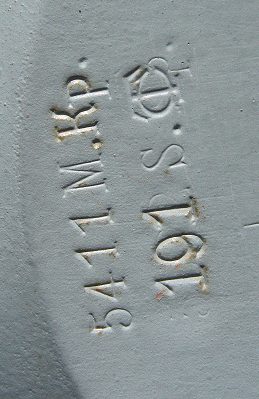

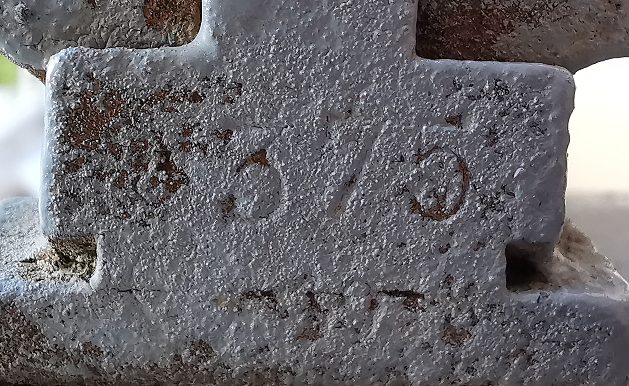

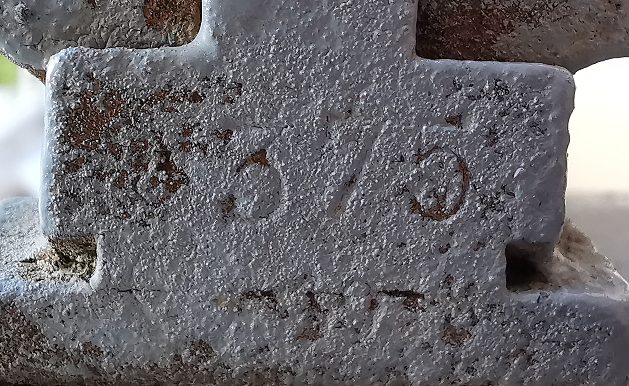

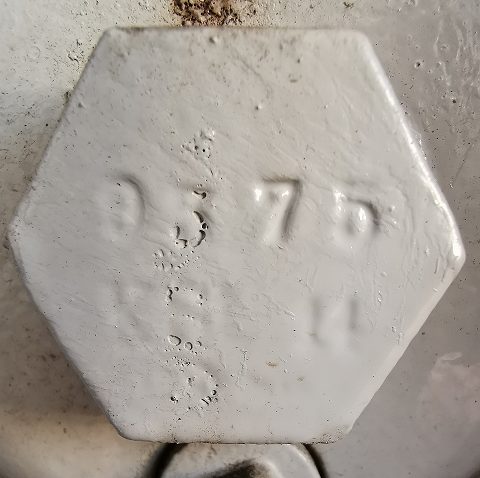

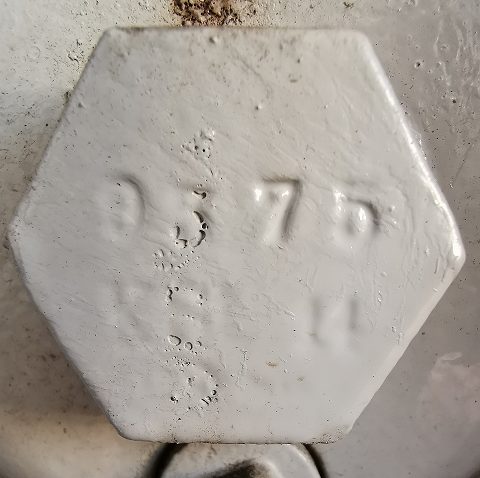

Many of the components which make up an ordnance have impressed markings for audit, tracking and identification purposes such as serial numbers, dates, manufacturer names/initials, and/or symbols, order numbers, inspector’s proofs and operating instructions.[15]Pearson (2000: 54). As components can be manufactured by a single manufacturer or multiple manufacturers, in one or more towns/factories over time, and the markings found on the surface of parts of the gun may reflect this history. Presumably, when an artillery piece is first assembled, its component markings are more likely to share a synchronic relationship; either the whole gun or parts of the gun have the same or similar markings, dates and serial numbers. Over time it is expected that artefacts such as guns, having been used as they were intended, will be either destroyed or damaged during operation service; either from counter offensive fire, deliberate destruction by their users or wear through use (use-wear). As parts are interchanged (through upgrades or damage) the relationship of the individual components and their markings is likely to become more diachronic or divergent to other ‘original’ components of the artefact; this is analogues to stratigraphical layers in an archaeological excavation were layers generally reflect the ordering of the deposits over time. However, in reality ‘original’ components and their markings may or may not be necessarily be found on an object in an ordered in a stratigraphic sequence (were ‘younger’ components or markings overlay older components or markings). Yet, stratigraphical sequencing can be observed in paint layers on components of guns where the older layers are found on the bottom layers and the layers get consecutively younger as the progress towards the top most layers. Intrusive layers of paint can invade other layers and if not understood can distort the evidence base (Figs. 25–26).[16]Pearson (1998); Pearson (2000); Pearson and Connah (2009). Obviously, this would seem to be especially prevalent to older guns that may have required the upgrading or replacement of components from damage or use-wear over time; whereas a gun produced near the end of the war is less likely, although not in every case, to have required newer or replacement componentry and its’ markings should ideally be more consistent. In addition, when systems are under pressure, deviations from normal procedures are more likely to occur. For example, near the end of the war, economic or operational requirements may have dictated the use of mixed and matched parts from worn out and battle damaged guns to be reused or recycled and this is reflected in the physical evidence. Thereby, creating hybridisation, cannibalisation or usual/abnormal combinations of components and/or markings.

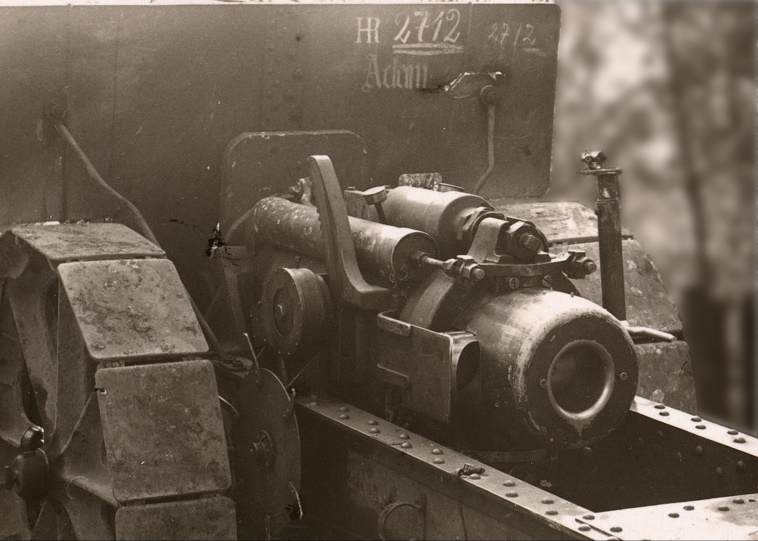

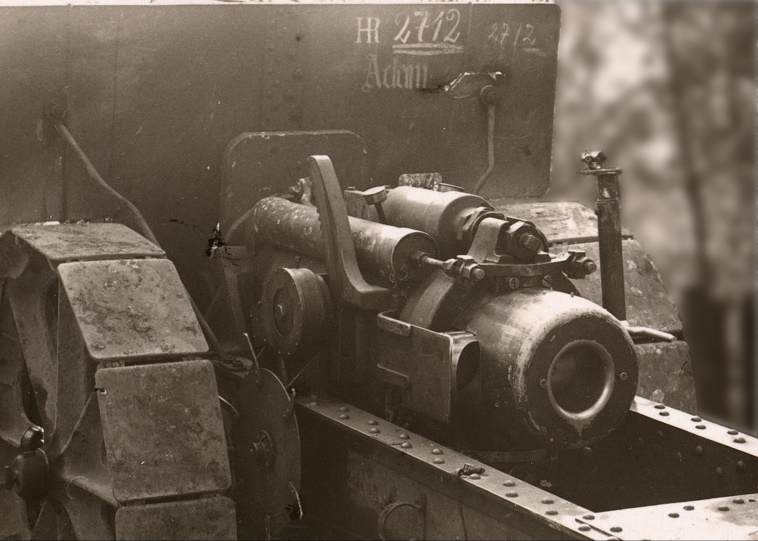

Some markings on gun components are more diagnostic, having meaning beyond the component level. For example, for most First World War German and Austro-Hungarian artillery the most informative evidence are the markings found around the breech-ring and sometimes the breech-block of the weapon. The barrel number (rohrnummer) following the ‘Nr.’ (nummer) marking on the breech-ring is usually considered the gun number for the purpose of recording or references to the whole artefact. The breech-ring, and sometimes the breech-block, are usually also marked with the year of production (jahreszahl der fertigung) and the producing company (fertigende firma) as well as in many instances having acceptance stamps (abnahmestempel), which may or may not be present on other components of the gun (Figs. 27–30). This is in contrast to other barrel components which are more transitory and can be replaced around the breech-ring. For examples, components such as the barrel tube (seenlenrohr), and the barrel jacket (mantelrohr) are frequently exchanged when worn through use or other damage and this information can be recorded on different parts of the breech-ring (Figs. 18 and 30). Considering the quantity of rounds that many of these guns may have fired, this replacement could have been a relatively frequent event.[17]Wear on barrels and other parts of guns must have been extreme. For example, Muther (1935b: 318) says that approximately 161,000,000 rds. (for field guns) and 66,000,000 rds. (for light howitzers) totalling 227,000,000 rds. which were sent into the … Continue reading When this occurs the markings on the new components and the breech-ring can change and become more complex through the accumulation of additional markings; numbers and symbols which prefix or suffix the original numbers as well as the over stamping of obsolete serial numbers. The location of some of these markings appear to be chronologically and stylistically based on a particular weapon type; the locations of similar markings are generally consistent within the same type but may be different on other types or between manufacturers (Figs. 27–30).

Similarly, the barrel number seems to supersede any additional markings found on the recoil cradle (rohrwiege) or gun carriage (lafette), which can also have serial numbers dates, and manufacturing details (Figs. 19–20). As an interchangeable components, many examples exist where the carriage and barrel components have very different dates, serial numbers and manufacturers, indicate replacement. This is in additional to the numerous smaller components which could be marked in different ways (Figs. 31–32). The carriage could also be interchangeable within other guns of a given type (or types that share the same components e.g. the carriage of the 7.7-cm F.K. 16 and 10.5-cm l.F.H. 16). Barrel components could also be replaced independently from the breech-ring and carriage components. Thus there are potentially infinite and complex combinations of markings to be ascertained from the objects based on its ‘life’ history.

The examination of markings on components is dependent on a number of factors such as the:

- nature of the marking: impressed, cast or welded into the surface of the component. Less common are original painted instructions, unit designations etc. and markings applied post depositional such as capture details in chalk, paint, stripped or scratched into surfaces (Figs. 33–34);

- Nature of the physical evidence (e.g. destructive processes that have damaged the artefact over time such as damage from battle, transportation, curation, or expose to the elements) affecting the:

-

- degree of survival of the markings (e.g. exposure to the elements and sandblasting removes painted markings; rust, other corrosion and grinding may remove impressed markings) (Figs. 21, 35–37);

- condition of the remaining evidence (rusted, deformed, or abraded surfaces) which occurred either pre- or post-discard or capture; and

-

- concealment of the markings. This could be due to a markings being:

-

- only in a visible location (Fig. 38–39);

- on the outside of a component (whereas markings on the inside of a component would only be visible if the component is disassembled);

- partially or totally obscured by multiple layers of paint (either original or non-original) applied to the surface of the artefact over the last 100 years (Fig. 40–41);

-

- Ability to read the markings which often result in indecipherable or partially decipherable markings (Fig. 42).

Thus, the evidence from the similar or different markings being used over time can show a new weapon through consistent marking or an older weapon through inconsistent markings from component replacement, cannibalisation, and hybridisation. It may also indicate operational tempo/demands and/or the lack of resources in which a particular weapon was a part.

Analysis of components & markings

A visual analysis of both components and their markings should be objective and based upon the evidence that is available and quantifiable. Such evidence should also be considered by examining patterns of markings, across multiple similar and dissimilar artefacts and/or where possible be corroborated by other primary sources. Date methods such as absolute and relative dating methods should ideally be applied if date data is available or there are known variables (e.g. year that the factory opened or moved, the year that the model was introduced, the production date and capture dates). However, even when such dating evidence is available (e.g. date markings on components) it does not provide an absolute date, as it only provides a reference to an entire year (unless the component is stamped with a day of manufacture on it or this evidence is available in another form such as a production leger). Even then component/s may have been manufactured earlier and date stamped later, or only date stamped during assembly. Earlier numbered or dated components might also have been used in the assembly or maintenance of a gun and on the basis of chronological ordering, it could be suggested that the gun thus becomes part of the context of the earlier component. This is not taken to be so for this analysis because without the larger component groups the smaller parts are purposeless as well as components are usable irrespective of the markings.[18]Pearson (2000: 58). Therefore, other relative dating evidence might be applicable which can refine the guns manufacture more precisely. For example, a gun with the 1918 manufacturing markings, which was captured in August of that year, provides a relative date range. In this example, the earliest time that this datable gun/component was manufactured (a terminus post quem) would be January 1918, and the latest would be August (a terminus ante quem). Because it would take some time for the gun to be shipped to the unit it was likely not to have been manufactured in July/August. Other evidence to further refine this date might be available if there is evidence for the date of unit formation or date that it had received new guns. Such relative dating techniques are essential when dealing with imprecise evidence unless original factory records or maintenance manuals can be sourced. Similarly, another relative dating example might be to establish when a newer pattern component or manufacturer was introduced, as well as when a stylistic or date ranges of serial numbers were introduced (Figs. 16, 43).

Consideration in the analysis process should also take into account factors such as the:

- Idiosyncrasy introduced by individual factories, base armourers or unit;

- Number of markings that can be found or recorded on any given artefact (e.g. excessive paint application on the artefact over time conceals markings);

- Consistency of the number of markings that can be recorded may not be uniform between artefacts given the evidence that survives or can be seen (e.g. the number of markings found on a given type of gun may not be visible or even consistent across examples of this gun type);

- Level of detail which is useful against the level of detail (or classification) that actually hinders the understanding the artefact (or groups of artefacts);

- the small size of this special interest field means there are limited community members available for conducting an exhaustive survey of all markings on all artefacts that still exist.

Therefore, for this study conscious decisions have been made whether to include or omit marking examples based on their perceived diagnostic utility or practicality to the survey. Furthermore, conclusions based on the frequency of artefact markings are not necessarily correct but are most likely better than those based on a single artefact. In this way artefacts which are not considered to be diagnostic can be read and elements of their cultural biographies can be reconstructed.

Despite these issues the creation of an index which clearly describes many of these markings, as a visual analysis of artillery pieces, helps us greatly to understand these artefacts from over 100 years ago. Much of this detail, which may have been recorded or was available to the users of these artefacts as common knowledge, seems to have disappeared. It is hoped that this survey can help reconstruct this knowledge and make it available to those who are interested in this highly specialised field. This is especially true if this information is shared amongst an interested community who systematically corrects, cross references and adds to this knowledgebase for the use of everyone who is interested in these markings.

Note: right and left are relative to the artefact when standing behind it looking forward in the direction of firing.

ORGANIZATION, ARMAMENT, AMMUNITION AND AMMUNITION EXPENDITURE OF THE GERMAN FIELD ARTILLERY DURING THE WORLD WAR BY LIEUT. GEN. VAN ALFRED MUTHER, Retired

Translation by Captain Arnold W. Shutte

IV AMMUNITION OF THE GERMAN FIELD ARTILLERY 1. THE AMMUNITION SITUATION AT THE BEGINNING OF THE WAR

References

| 1⇧ | Harley (1987); Gosden and Marshall (1999); Kopytoff (2010); Cornish (2004); Stengs (2005). |

|---|---|

| 2⇧ | Pearson (2000); Connah and Pearson (2002); Pearson and Connah (2009); Pearson and Connah (2013); Pearson and Browning (2015); Pearson and Vanderkelen (2018); Pearson (2019: 462–469). |

| 3⇧ | Pearson (2000: 51). |

| 4⇧ | Die feldkanone 16. (F. K. 16) (H. Div. 445). 1. Teil. Das feldkanonenrohr 16. 1926 (p.12); Die leichte feldhaubitz 16. (l.F.H. 16.) (H. Div. 446.). 1. Teil Das leichte feldhaubitzrohr 16. 1926 (p.12); Der Artillerist I (Der Kanonier). 1941 (p.151–152). |

| 5⇧ | For example, Great Britain distributed two pools of ceded (surrendered) and unclaimed guns between 1919 and 1920. These were divided up between Great Britain and all the dominions involved in the fighting. Pool 1 consisted of a total of 1036 guns available for immediate distribution (822 ceded and 214 unclaimed); which was only about one third of the number of total ceded guns available to Great Britain. Of these 880 were distributed to Great Britain; 60 guns to Australia and 60 to Canada; 30 to India; 12 to New Zealand and 12 to South Africa; and 12 distributed to other colonies. An additional 1600 guns were serviceable but not available at the time. Pool 2, consisting of the total remainder of guns, consisted of approximately 2500 guns (AWM16 4386/1/84; AWM16 4386/1/95; AWM22 739/6/3; AWM93 27/1/103; AWM93 27/1/153). |

| 6⇧ | For example, Muther (1935a: 201, 210) says at the end of the war in November 1918 there were 2,800 Field Artillery Batteries totalling 11,204 guns and howitzers. A breakdown of the types was as follows: ‘755 Batteries with field gun 16 [7.7-cm F.K. 16]; 751 Batteries with field howitzer 16 [10.5-cm l.F.H. 16]; 66 Batteries with field howitzer Krupp; 936 Batteries with field gun 96 n/A [7.7-cm F.K. 96 n/A.]; 286 Batteries with field howitzer 98/09 [10.5-cm l.F.H. 98/09]; 6 Batteries with experimental models; Totals, 2,800 Batteries with 11,204 guns’. In addition, Muther (1935a: 211) says in relation to Mountain Artillery, there were: ‘21 mountain batteries, including 17 gun and 4 howitzer batteries …[totalling] about 100 guns…’; Infantry Cannon: ‘50 Infantry Batteries … comprising some 200 guns’; Anti-tank: ‘Fifty “close combat Batteries” with 200 guns were set up in January, 1917. In addition: (a) 200 2 cm, Anti-tank guns Erhardt & Becker. (b) 600. 3.7 cm. Anti-tank guns Erhardt & Krupp. (c) 150 Belgian 5.7 cm. casemate guns mounted on 4-ton trucks as Anti-tank guns’; Anti-aircraft guns: ‘3,000 anti-aircraft guns were produced during the course of the war’. |

| 7⇧ | Part V, article 165 of the Treaty of Versailles set strict limitations of 204 7.7-cm guns and 84 10.5-cm Howitzers which could be retained by the German army, many of these guns would consequently be destroyed during the Second World War (Treaty of Peace with Germany – 28 June 1919: Article 165: p.117 and Table 3, p. 123 https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0043.pdf ). |

| 8⇧ | Australian, in spite of the distance and expense of transportation from Britain and Egypt, collected: ‘about 800 guns, 3800 machine guns, 520 trench mortars, 217 motor vehicles, a number of horse vehicles’ [and] tanks’ (CAPD 1917–19: 14,007–14,008; Clayton 1995a: 19; 1995b: 19; 1996: 5; Pearson and Connah 2013: 43). However, the number of guns and machine guns that were transported to Australia is known to have been higher (RAAHC Artillery Register). In relation to the total number of guns returned to Australia, on the 27 March 1919 it was noted that Australian troops claimed to have captured the following Guns of various types: 369 from France, 271 from Egypt; MGs: 2,268 from France, 933 from Egypt; Trench Mortars: 320 from France, 37 from Egypt (AWM16 4386/1/95). On the 1 September 1919 the number was larger (only noted for France), Guns: 383; MGs 2,700; Trench Mortars 393 (AWM16 4386/1/28). On the 25 September 1919 the number of Guns (from France) was again increased, this time to 408 (AWM93 27/1/93 or 27/1/153?). A report dated 3 October 1919 gives additional figures, ‘As an indication of the magnitude and range of collection, it may be mentioned that it includes nearly 700 guns, 3000 machine guns, 500 trench mortars, and 10 aeroplanes …’ (AWM93 27/1/180). These figures probably include a number of guns that the Australian Government was offered from two pools of ceded (surrendered) and unclaimed guns mentioned above in 1919 to 1920. Australia’s proportional share from Pool 1 was 60 guns from a total of 1036 (AWM16 4386/1/95). These 60 guns were received (AWM16 4386/1/84; AWM93 27/1/153). Australia’s share from Pool 2 was between 140–250 from approximately 2500 guns (AWM16 4386/1/84; AWM16 4386/1/95; AWM22 739/6/3; AWM93 27/1/103; AWM93 27/1/153). It appears that at least 50 guns were accepted and many of the other guns were noted as only good for scrap (AWM93 27/1/153). Moreover, at least 22 guns (French and German) were also gifted to Australia from the French Government (AWM16 4386/1/123; AWM262; The Mercury, 13 September 1921: 4; The Argus, 10 October 1921:8). There also appears that there were at least three guns from the Italian front (AWM262). On 27 May 1919 it was stated that there were 16 captured guns in Australia (presumably official ones) and by September 1919 this number had increased to 250 (AWM93 7/4/424; AWM93 27/1/153). All of these figures illustrate how difficult it is to acquire definitive return figures. Most of these items, particularly the guns, were distributed to Australian cities, towns, and Army units for display (AWM93 7/4/440; AWM93 27/1/153; AWM194: AWM262; Billet 1999). In addition, some formed the nucleus of the subsequent museum at the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra. In later years some of the guns were melted down during World War II (Daily Telegraph, 13 February 1942: 1), potentially reused, or treated as a source of particular parts (NAA SP1008/1 484/1/706A; The Herald, 4 April 1942: 5; Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 1942: 10). Some were even buried to get rid of them (The Argus, 7 April 1937: 8; Clayton, 1996: 23–24; Billett, 1999: 49; Hunter, 2007: 13–16; Browning et al., 2008: 480), some were subsequently acquired by private individuals, and many are now unaccounted for. Although a considerable number are known to have survived, most of them have spent many years in an outdoor environment, often in public parks, and have seriously deteriorated (Browning et al., 2008; Passion and Compassion 1914–18; RAAHC Gun Register). |

| 9⇧ | The Canadian ‘Report of the Award of War Trophies’ dated 18 May 1920 listed: ‘516 captured German guns and howitzers, 304 trench mortars, 2,500 heavy and light machine guns …’ Skaarup (2013: 15). However, a report of December 1942 says that 305 Field Guns, 111 trench mortars, 217 machine guns and other cannon had been sent for scrap (Skaarup 2013: 15). ALSO ADD CANDIAN ARCHIVE REFERENCE + ARTICLE (Library and Archives Canada, RG 37 Vol. 688) |

| 10⇧ | Cooke and Maxwell (2013: 48) say that by mid-1919 the NZEF had claimed 165 guns, in addition to guns from Pool 1 and 2. Appendix 2 in Cooke and Maxwell (2013: 424–435) lists entries for 220 guns (from France and Palestine), and 136 Trench Mortars derived from multiple archives files. |

| 11⇧ | America, for instance, although a latecomer to the conflict, appears to have collected the most, including 3,242 captured pieces of artillery, 4,550 vehicles, 347 aircraft, and other items (Kahn 1921: 5). |

| 12⇧ | Although beyond the scope of this work, but mentioned above, also includes other evidence available from components such as the application of paint, graffiti, and damage from action, movement and storage as well as changes resulting from later curation (Pearson and Connah 2009: 234). |

| 13⇧ | Pearson and Connah (2009: 236). |

| 14⇧ | n/A. (New art or new model). |

| 15⇧ | Pearson (2000: 54). |

| 16⇧ | Pearson (1998); Pearson (2000); Pearson and Connah (2009). |

| 17⇧ | Wear on barrels and other parts of guns must have been extreme. For example, Muther (1935b: 318) says that approximately 161,000,000 rds. (for field guns) and 66,000,000 rds. (for light howitzers) totalling 227,000,000 rds. which were sent into the field for both field guns and light howitzers (not including Foot Artillery). The translator of this article, Captain Slatter, in a note at the end of the article says that this would equal: ‘per month, of 11,634,240 rounds; per day, of 387,808 rounds; per hour, of 16,150 rounds; per minute, of 269 rounds; per second, of 4½ rounds’ (Muther 1935b: 319). |

| 18⇧ | Pearson (2000: 58). |